The Innovation Paradox: Why You Can't Measure a Paradigm Shift

We are obsessed with validation. But while data is excellent at optimising the present, it is often terrible at predicting the future. True innovation requires swapping the safety of metrics for the risk of conviction.

In the modern Product Management universe, “Data-Driven” has become a religious mantra. We don’t just use data; we rely on it to absolve us of responsibility. We want A/B tests, validation metrics, and market signals to tell us exactly what to build next.

It feels safe. It feels scientific. But there is a dangerous ceiling to this approach. A friend recently mentioned a thought that really stuck with me:

“No great achievement would have ever survived a cost-benefit analysis.”

This isn’t just about money; it’s about certainty. If you wait for the data to prove that a paradigm shift is definitely going to be a “good idea”, you have already missed the boat. Data is a record of the past, and you cannot measure the performance of a product that creates a behaviour that doesn’t exist yet.

The Trap of the Local Maximum

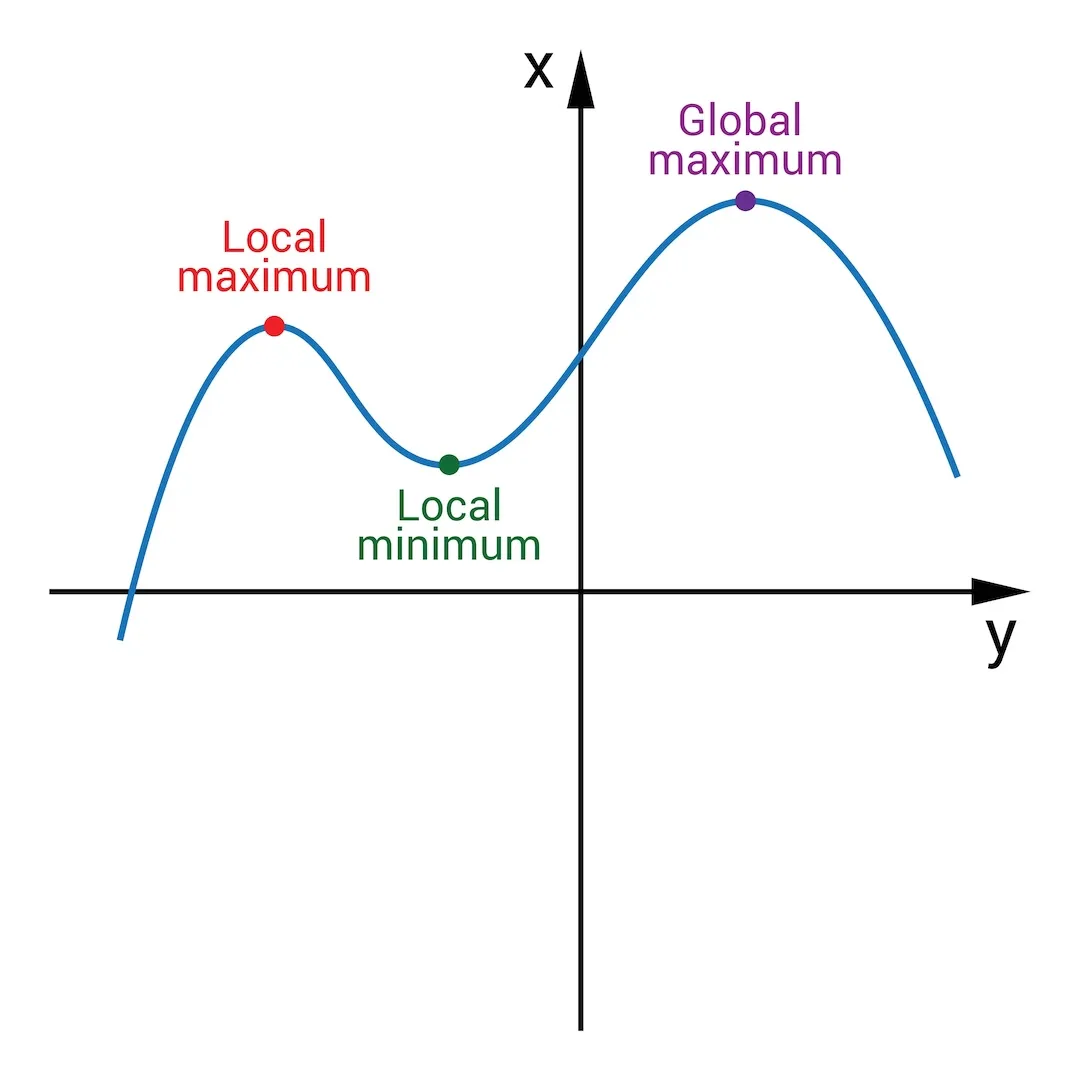

In product theory, we often talk about the Local Maximum.

Figure 1: Graph illustrating the local maximum versus the global maximum.

Figure 1: Graph illustrating the local maximum versus the global maximum.

Imagine you are climbing a hill in the fog. You use your data (your altimeter) to make sure every step you take is “up”. You optimise your path perfectly, eventually reaching the very top of the hill. The data says you can go no higher. You have reached the peak.

But because of the fog (the unknown future), you can’t see that you are standing on a small foothill, and right next to you is a massive mountain that soars ten times higher.

This is what a purely data-driven approach does. It is incredible at optimisation (climbing the current hill). It is terrible at innovation (going back down the valley to climb the next mountain).

- Data could tell Blockbuster how to optimise late fees and store layouts.

- Data could not tell them to abandon their stores and start a streaming service.

To move from the foothill to the mountain requires a temporary drop in metrics. It requires a leap of faith across the gap.

The Innovation Gap: Lessons from the Walkman

This is where the “Product Manager as Scientist” metaphor breaks down. In science, you observe existing phenomena. In innovation, you are trying to create new phenomena.

Consider the famous case of the Sony Walkman. In the late 1970s, market research was explicitly clear: consumers did not want a cassette player that couldn’t record. It was a “broken” product. The data was accurate regarding current consumer expectations, but it was blind to future potential.

Akio Morita, Sony’s co-founder, famously ignored the research. He didn’t have data; he had a conviction. As noted in innovation case studies, Morita believed that people loved music enough to want it with them everywhere, even if they couldn’t articulate it yet. He made a unilateral decision to launch, stating, “The market research is in my head.”

If he had waited for the data to validate his decision, the Walkman would never have existed.

Discovery is Not Taking Orders

Does this mean we should abandon research and just guess? Absolutely not.

The mistake many organisations make is treating research as a way to ask customers for solutions. If you ask a user what they want, they will describe a slightly better version of what they already have (a faster horse).

True Product Discovery isn’t about gathering requirements; it’s about uncovering unknown opportunities.

- Don’t ask: “Would you buy a portable cassette player that doesn’t record?” (They will say no).

- Do observe: How often do people struggle to listen to music while travelling? How does music change their mood? Where are the gaps in their current experience?

We must utilise qualitative research, observation, and deep discovery to understand the Problem Space intimately. But when it comes to the Solution Space, we cannot expect the customer to lead us. That is our job.

Conviction vs. Validation

This brings us to the core conflict in modern product leadership: the battle between Validation and Conviction.

Validation is the act of asking the world to confirm you are right. It is external. It seeks safety in numbers. It is the tool of the optimiser.

Conviction is the act of believing you are right before the world agrees. It is internal. It accepts the risk of being wrong in exchange for the chance to be transformative.

This is why true innovation is rare. It isn’t a resource problem; it’s a courage problem. When you lead with conviction, you strip away the protection of the spreadsheet. You are saying, “The data doesn’t see this yet, but I do.” You are putting your reputation on the line.

Leading Through the Fog

We shouldn’t discard data. We just need to understand its role.

- Data is for Navigation: It tells you where you are and how to optimise your current path.

- Conviction is for Destination: It tells you where you need to go, even when the path isn’t visible.

The best product leaders are Conviction-Led and Data-Informed. They prioritise research to understand the human struggle, but they do not expect research to design the solution.

To achieve something great, you have to accept that for a long time, the spreadsheet will look ugly. You have to be willing to walk down the hill to find the mountain.

Homework: Look at your current roadmap. Are you only building things that you can prove will work? If so, you might be optimising your way to a dead end.