Speak Up, Write It Down, Put It Out There

Why forcing yourself to articulate your thinking is the most underrated skill in your career. From rubber duck debugging to publishing online, the mechanism is the same: saying it out loud makes the thinking better.

Early in my career, I received a piece of feedback that stuck with me. It was the kind of thing that stings a little because you know it’s true:

“I would like Steve to be more forceful and vocal in meetings. In my eyes it appears that Steve providing his insights earlier in discussions could at times ‘short-cut’ meetings.”

I knew immediately he was right. It wasn’t one of those bits of feedback you file away and rediscover years later with fresh eyes. It landed with the uncomfortable clarity of something I’d already been half-aware of. I’d sit in meetings, form thoughts, wait for the perfect moment to contribute, and then watch as the conversation moved on without me. Or I’d speak up late, only to find that the group had already landed on what I’d been thinking ten minutes earlier. The feedback didn’t tell me anything new. It just said it out loud, which, ironically, is exactly what I’d been failing to do.

That realisation sent me down a path I’m still on: articulating my thinking, out loud, to other people, in writing, in public, because it changes the quality of the thinking itself.

Why putting your thinking out there matters

Let’s start with what happens when people do articulate their thinking, both for themselves and for the people around them.

According to a Salesforce study reported in Inc., employees who feel their voice is heard at work are 4.6 times more likely to feel empowered to perform their best work. That’s not just a nice-to-have. It suggests that the act of contributing, and being received, fundamentally changes how people experience their own capability. Meanwhile, Grammarly’s State of Business Communication report found that 66% of knowledge workers and 72% of leaders wish their organisations would invest in tools to help them communicate more effectively. The appetite is there. People want to share their thinking. The friction is in the how.

Deb Liu, author of Take Back Your Power, captures a version of this tension. She tells the story of a talented colleague who kept getting overlooked: “Every time she came up for promotion or calibration, people were like, ‘Oh, what does she do?’ And it was because she was not good at broadcasting or explaining what she does.” This isn’t a story about someone who lacked insight. It’s a story about insight that never made it out of one person’s head and into the space where others could benefit from it.

That’s the real opportunity here. Articulating your thinking doesn’t just help your career, though it does that too. It sharpens the thinking itself. Every thought you put into words is a thought you’ve been forced to examine, structure, and stress-test. And every thought you share is one that other people can build on, challenge, or redirect. The value isn’t just in being heard. It’s in what the act of speaking does to the quality of your ideas.

Why articulation changes your thinking

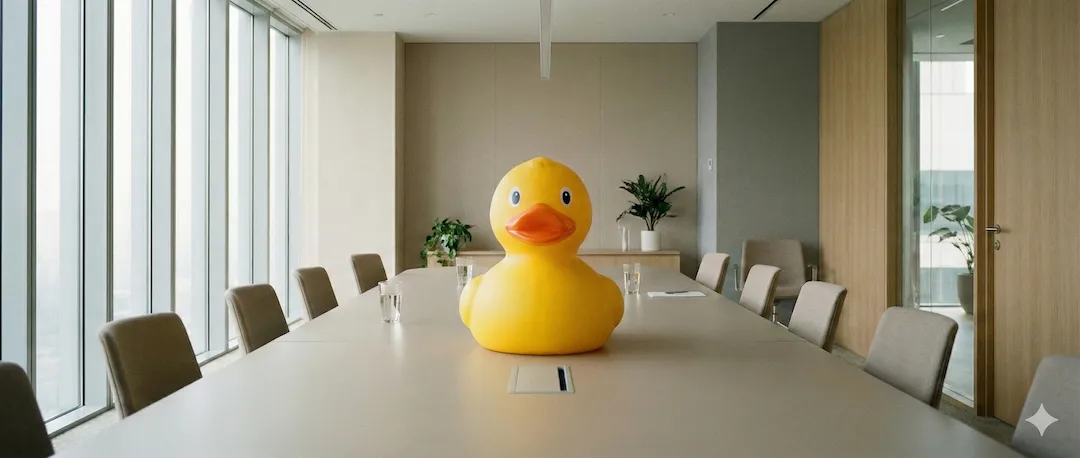

Here’s where things get interesting. Software engineers have known this for decades, through a concept called rubber duck debugging.

The idea, widely attributed to The Pragmatic Programmer by Andrew Hunt and David Thomas, is beautifully simple: when you’re stuck on a bug, you explain your problem aloud to a rubber duck. That’s it. You talk to a duck.

It sounds absurd, but it works because of something fundamental about how our brains process information. When you’re scanning code silently, you’re in “pattern-matching mode”, your eyes are moving, you feel productive, but you’re glossing over assumptions. The moment you force yourself to explain the problem step by step, as if to someone who knows nothing about your code, you shift into “explaining mode.” You have to be explicit about what you think is happening versus what’s actually happening. And that’s usually where the flaw reveals itself.

Many developers find they solve the problem halfway through explaining it. Sometimes before they even finish the question. It’s also why posting a question on Stack Overflow and then immediately finding the answer yourself is such a universal experience. The discipline of framing the problem clearly is often all it takes.

This isn’t a programming trick. It’s a thinking trick. And it maps directly onto that meeting feedback I received. I was doing the silent equivalent of scanning code, processing information internally, pattern-matching, feeling like I was contributing by listening carefully. But the act of forcing my thoughts into words, into the room, would have sharpened them in ways that internal processing simply couldn’t.

Getting started (when it feels impossible)

If you’re reading this and thinking “that’s easy for you to say,” I hear you. Speaking up is genuinely uncomfortable, especially in environments where you feel junior, uncertain, or simply outnumbered.

So how do you actually start? Claire Hughes Johnson, in her book Scaling People, offers a deceptively simple entry point: ask a question. A question is not threatening. It doesn’t require you to have the answer. It just forces the room to examine an assumption. That’s the meeting equivalent of rubber ducking. You’re not declaring anything. You’re just making implicit thinking explicit.

The fear, of course, is that you’ll stumble. That you’ll start a sentence and lose the thread halfway through, and everyone will notice. But research on the peak-end rule suggests otherwise: people remember how an experience ends far more than how it begins. That awkward pause where you gathered your thoughts? Nobody remembers it. They remember where you landed.

And here’s the thing that took me longest to learn: the words matter less than you think. What matters is whether you’re genuinely present in the conversation or holding back out of self-protection. People can tell the difference. A half-formed thought offered with genuine curiosity lands better than a polished point delivered defensively. The barrier to speaking up is almost always internal, and the cost of staying silent is almost always higher than you think.

The introvert question

Everything I’ve said so far assumes a fairly specific kind of person: someone who has thoughts but holds them back. But not everyone processes information the same way. Some people think by talking. Others think by reflecting. Telling introverts to “just speak up more” can feel like telling left-handed people to write with their right hand.

Donna Lichaw, in her book The Leader’s Journey, tells the story of a leader who “was so quiet that her team thought she was not interested in them… it really was detrimental to them all working together.” But the solution wasn’t to force her into a different personality. It was communication about process: “She just started communicating with them more about, ‘Hey, this is my style. I’m a little slower. I often need a couple of hours to really process things. I’m here, and I want you to know that.’”

This feels like a crucial middle path. The goal isn’t to turn everyone into the loudest person in the room. It’s to make your thinking visible, whatever that looks like for you. For some people, that’s speaking up in the moment. For others, it’s following up after with a considered email. For others still, it’s writing.

From speaking up to writing it down

Deb Liu’s manager gave her a piece of advice that changed her career trajectory: “Just write what you repeat. If you say something more than once, just write it down.”

This led to years of monthly internal posts, which eventually became external publishing, and ultimately her book. The progression is worth examining: she didn’t start by writing for the public. She started by capturing thoughts she was already having and putting them somewhere others could find them.

Ed Elson, on a recent podcast with Kyla Scanlon, pushes this idea further:

“If you want to connect the dots and be smarter about what is happening in the world, you should just make yourself speak more. Like, you should say more things at work. When you’re in a meeting, you should just force yourself to say something, have an opinion.”

And then the leap to public:

“You should do it online. Like, you should post on LinkedIn. You should start a newsletter. Like, I feel like the more you hold yourself accountable to producing thoughts and ideas, which is really uncomfortable to do, but the more you force yourself to do it, I think it really helps you connect the dots and also develop your own perspective.”

What Ed is describing is rubber ducking at scale. When you write for an audience, even a small one, you’re forced to examine your assumptions more rigorously than when the thoughts stay in your head. You have to structure your argument. You have to anticipate objections. You have to decide what you actually believe versus what you’re merely parroting from someone else.

The accountability mechanism matters too. Deb Liu had a monthly cadence. Ed talks about holding yourself accountable to “producing thoughts and ideas.” The regularity is what transforms occasional insight into a consistent practice of thinking clearly.

The critical caveat: informed takes, not hot takes

Now, I know what you might be thinking. Doesn’t the internet already have enough people sharing their opinions? Do we really need more LinkedIn posts?

Kyla Scanlon provides the essential correction:

“I don’t know if we need like more hot takes. I think we need more informed takes.”

This is the distinction that separates valuable public thinking from noise. Hot takes can spark lively debate and provide fresh perspectives, but they also run the risk of oversimplifying complex issues or sensationalising topics for clicks.

And to be clear, none of this is an argument for speaking up purely for the sake of being heard. If you’re in a meeting about a topic you know nothing about, interrupting the conversation just to register your presence helps nobody. That’s not articulation, it’s performance. The goal is to share thinking that you’ve actually done, not to fill silence with sound. There’s a meaningful difference between “I haven’t spoken yet so I should say something” and “I have a perspective here that might be useful.”

But here’s where the rubber duck metaphor becomes particularly powerful. The whole point of rubber ducking is that it forces you to slow down and examine your assumptions before you present your conclusion. The discipline of articulating your thinking carefully, whether to a duck, a colleague, or a LinkedIn audience, is itself the preparation that transforms a hot take into an informed one.

The answer isn’t “share less.” It’s “think more before you share.” And the best way to think more is, paradoxically, to commit to sharing regularly, because that commitment forces the preparation.

A progression, not a leap

Looking back at all of this, I think the real insight is that speaking up isn’t a single skill. It’s a progression:

-

Talk to the duck. When you’re stuck on a problem, explain it out loud. To a colleague, to a rubber duck, to your dog. The act of articulating the problem will often reveal the solution.

-

Speak in the room. In meetings, force yourself to contribute earlier. Ask a question. Share an observation. Own it as your perspective, not a universal truth. The thought you’re holding back might be the one that short-cuts the entire discussion.

-

Write what you repeat. If you find yourself making the same point in multiple conversations, write it down. Share it internally. You’re already doing the thinking; capturing it creates leverage.

-

Put it out there. When you’ve built confidence in your perspective through the earlier stages, share it publicly. Start a newsletter. Post on LinkedIn. The accountability of a public audience will sharpen your thinking further.

Each stage builds on the last. Each one involves a slightly larger audience and a slightly higher bar for clarity. And each one delivers the same core benefit: forcing yourself to articulate your thinking makes the thinking better.

Back to the feedback

I think about that career feedback sometimes. Not because it took me ages to absorb, it didn’t. But because understanding something intellectually and actually changing your behaviour are two very different things. Knowing you should speak up earlier in meetings is easy. Doing it, consistently, when every instinct is telling you to wait, to refine, to hold back until you’re certain, that’s the work.

Rubber duck debugging works because it forces you to be explicit about what you think is true. Speaking up in meetings works for the same reason. Writing works for the same reason. Publishing works for the same reason.

The medium changes. The mechanism doesn’t.

So speak up. Write it down. Put it out there. Not because the world needs more noise, but because your thinking deserves to be examined, and the only way to examine it properly is to say it out loud.